2014 Minnesota Vikings NFL Draft: Scouting Aaron Murray

Aaron Murray has been developing a lot of momentum lately, especially among Vikings fans—should an elite prospect like Khalil Mack or even Sammy Watkins be available at pick eight, perhaps the Vikings could take that talent and then take a prospect later in the draft who could fill the same position.

If it were the case that the quarterbacks in the third or fourth round are not significantly different than the ones in the first round, this would be a pretty awesome strategy—and Aaron Murray is central to a lot of plans Vikings fans have envisioned. He has been a statistical maven (the SEC passing yards and touchdown leader and the 2012 yards per attempt and adjusted yards per attempt leader in all of the FBS), and with a merely “OK” supporting cast, to boot—the undraftable Rantavious Wooten, mid-round prospect Arthur Lynch and a number of receivers who don’t look promising for next year’s draft—not to mention countless injuries at skill positions, including the loss of Todd Gurley, one of the nation’s premier running backs.

Reputed to be a smart, accurate quarterback who’s played in college’s “toughest” division, what’s not to like?

Accuracy: It’s been easy for him to be accurate at the college level in terms of getting the ball to the receiver, but he is far too erratic in terms of putting the ball in a space with exclusive real estate to his players and has a number of balls overthrown, underthrown, thrown too far behind and too far ahead of his receiver to really be called “accurate”.

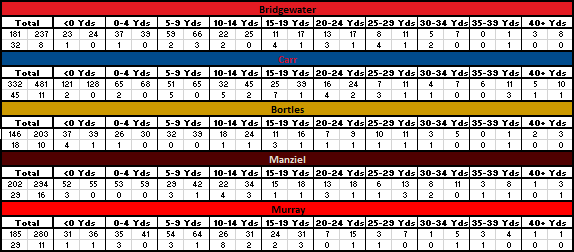

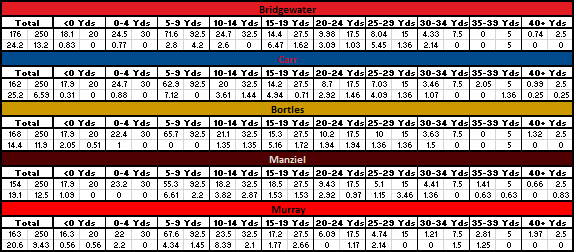

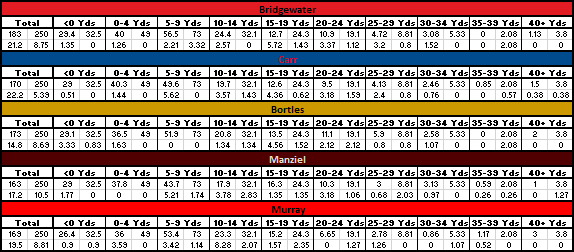

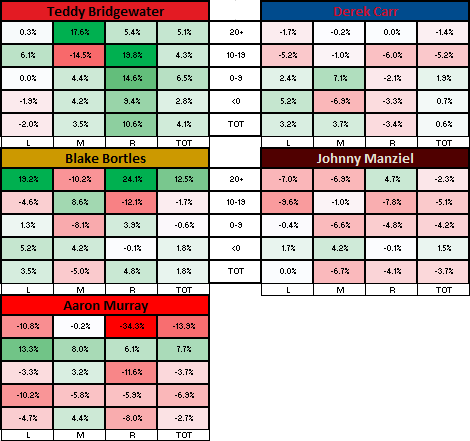

In fact, even at the base level of getting the ball to his receiver, Murray falls behind the others in his class. One can look at a passing chart created of Murray over seven games (Clemson, Florida, Missouri, Tennessee, LSU, Auburn, South Carolina) and compare it to the passing charts of the other four I’ve done charting work for, as well as the modified charts that adjusts attempts for system:

Murray is not inaccurate in this context, but a player considered “accurate” should significantly beat his peers. His ball placement is a big concern and could hamper an offense in a big way. He seems to have a sense of who will be open, but not a precise understanding of where they will be. Alternatively, he simply could not be that accurate.

If that’s the case, there’s not a lot that can be “fixed,” as he doesn’t have a lot of accuracy-related mechanical issues that will resolve this level of relative inaccuracy, though he does have mechanical work that needs to be done.

Relative to the rest of the class, his passing on the run is a bit better (though not as good as Bridgewater, Manziel or Bortles) when rolling to his right, but one of the worst in the class when rolling to his left. From a distance perspective, he really flags in deep accuracy.

It’s difficult to tell with the charts above, but he is one of the worst in the class at deep shots. The five attempts tracked at 35+ don’t tell the whole story; the 32 attempts at 20+ do begin to paint a better (though not great) picture, though. Bortles is at the top of the tracked quarterbacks at 73.3% (32 attempts), Bridgewater follows at 65.9% (44 attempts) and Carr and Manziel follow shortly after with 59.4% (64 attempts) and 58.5% (53 attempts). Murray, on the other hand fell to 46.9%.

Overall, I was disappointed with Murray’s general accuracy because his reputation demanded more.

Delivery: Murray will have a long, looping delivery at times, and compact at others. To compound that, he will occasionally tip his hand by shaking the ball before throwing. I’ve found his release to elongate more often in games where he’s been hit often (like early on against Clemson, or later in the season against LSU), and that may speak to mechanical issues that will be exposed more often at the next level—even in live games, it is easier to hide ingrained muscle memory at the college level than in the NFL.

I really like his footwork when throwing, but haven’t seen enough of it coming out of a drop. Murray has fantastic rotation and setup with his base. He has great follow-through with his shoulders and hips to put power on the ball. Unfortunately, his variable release means that the timing of his footwork can be off and hurt accuracy on his throws. When his motion is tight, he steps forward into the throw. When his motion is longer, his lead foot hits the ground while he’s still cocking the ball back and he loses a lot of potential energy. Tom Brady, who sometimes has an elongated release that dips low (though not below the hip, like Murray), does not have this issue with his footwork.

Compare to Peyton Manning, whose high carriage combined with compact motion keeps the ball at a high chest level

This isn’t to say Murray always has a long, looping motion. There are a number of times that he keeps it compact and carries the ball high throughout the throw.

He has an issue with balls batted down at the line of scrimmage; it seemed like it happened once or twice in every game I scouted. Some of this has to do with his general throwing—the nose drives the ball down further than it should—and some of it has to do with his long release. A player like Blake Bortles, at 6’5”, doesn’t have to worry about this as much but Murray has to watch out a little bit more because of his long release and the fact that he doesn’t slide into throwing lanes (more important at 6’0 1/2”).

In general, he can throw from multiple platforms, and will sometimes willfully change his release in order to gain an advantage—a great thing, though a little odd that he can’t keep a consistent or even good release in normal throwing situations. The ball he throws would generally be catchable when accurate, but the trajectory problems that force the ball too low or too high make it very difficult for his receivers to get to the ball. This is part of the reason that Murray’s drop rate (14%) is higher than anyone else I’ve tracked so far, even after adjusting for distances (for reference: Bridgewater: 6.5%, Carr: 12.7%, Bortles 9.6%, Manziel 8.0%).

One final note, I’m not an expert in delivery mechanics, but it sure seems like Murray hasn’t nailed down when to let go of the ball or consistently pushes it away with his fingers in the same way—sometimes the ball will leave his hand with the nose too high, while at other times it will leave with the nose pointed far too low. This affects the trajectory of the ball in significant ways, and when this happens, Murray’s throws are wildly off target.

Ball Velocity: This is less important for Murray than it is a number of other quarterbacks in this class, but the point should be made here: arm strength matters.

It has recently become vogue to denigrate arm strength as an evaluative tool, and that makes sense. It certainly is not as valuable as the NFL seems to make it out to be when they draft poorly trained, strong-armed throwers over precise, weak-armed throwers. But that does not mean it is valueless, and the move to get away from traditionalists who value Giovanni Carmazzi over players like Tom Brady may have overcorrected.

This is not to say it is the primary evaluative criteria or that the NFL values arm strength correctly (I think they overrate it in practice—during the draft), but it isn’t irrelevant by any means.

It is critical that quarterbacks at least possess sufficient arm strength. Certainly, after a threshold, marginal increases in arm strength do not provide as much value as marginal increases in other traits. But that does not mean it is “less important” than other obviously key traits, like pocket presence and accuracy. Both of those can be “threshold” traits as well, where a sufficient amount in one can be good enough to lead a successful franchise. The difference, of course, is that most draft-eligible quarterbacks possess NFL-sufficient arm strength, but not necessarily NFL-sufficient pocket presence or accuracy.

Further, marginal increases in accuracy help a quarterback more than marginal increases in arm strength after a certain point. The reason that a quarterback needs to have appropriate arm strength is not the reason that many discuss: deep ball passing (though it certainly helps there). There are very few college prospects that cannot throw the ball 50 yards or more. Instead, there are a number of other reasons the emphasis on ball velocity makes sense.

The first is simply the size of the throwing windows in the NFL. Holes in coverage are smaller and the space between defenders will close faster at the next level, so the ball has to rocket through those small spaces, even on a seven-yard crossing route. A slower ball has no chance to get throw multiple closing windows.

Beyond that, most NFL offenses have an element of timing in them, which means that the receivers know when the ball should be coming, but the defense has to react. A slower ball gives the defense more time to react and make a play on the ball. Leveling the playing field in that manner is deadly for an offense.

A strong arm also makes deep shots more reliable by flattening the throws and giving the throws more consistency and predictability for the offense and threatening the entire field for the defense. A defense that only has to defend some of the field is an effective defense.

The ability to flick the wrist and still make a high velocity throw also reduces the margin for error for a lot of quarterbacks. Nearly any quarterback can make a top-tier throw in a clean pocket with time and room, but it takes a lot of skill and technical precision to reset ones’ self before throwing again with less than a second of time to adjust. Most quarterbacks, even in the NFL, do not fully have that skill. Arm strength can make up for it and give more wiggle room when dealing with these issues, artificially boosting accuracy and performance under pressure.

Taking the time to reset is an extremely difficult skill to learn and maintaining good mechanics when moved off of one’s spot is tough. Arm strength covers some of those difficulties up, and allows QBs not only to make an accurate throw, but create some consistency and hit spots on the field they otherwise wouldn’t be able to. This is also useful when it comes to throwing on the run, switching to hot routes on blitzes and throwing the ball away under pressure.

The last reason arm strength matters is not as significant as you might think given the conditions Minnesota will have to play in, but can be important: weather. Driving the ball through strong winds requires not just velocity (which great mechanics can help provide, but it’s something arm strength becomes important for) but a good spiral that catches less in the wind. Even pockets of air in domes can hinder ball movement, though at the NFL level it’s a minor effect.

An OK indicator of ball velocity comes from the radar gun at the Combine, and @AllbrightNFL has pointed out, no quarterback has thrown below 55 miles per hour at the Combine and succeeded in the NFL. It’s not a complete proxy for arm strength, as big guns like Joe Flacco (who actually threw at 55 MPH) don’t score as high as you’d expect. More importantly, not all quarterbacks get tested with a radar gun or are attempting to drive the ball the same. Still, it’s an interesting point in the evolving debate about arm strength.

At times, Murray feels like he’s riding the line in terms of arm strength and I worry that it’s not “sufficient” to get the job done, even if he was an extremely accurate quarterback (he’s not). As Sigmund Bloom and Matt Waldman point out in the Football Guys podcast, there could be an interesting discussion involving players with weak arms like David Fales—if it’s a threshold issue, then players like Fales are out of the discussion.

But if there’s a sliding scale between arm strength and accurate anticipation (and players like Peyton Manning and arguably Tom Brady prove there could very well be), then Fales could be in the conversation as a legitimate starter. Unfortunately, Murray is not yet at that point. If he were sufficient at one of the two skills, he would definitely be intriguing, but he is arguably not strong enough or accurate enough.

That isn’t a death knell. Tom Brady, Aaron Rodgers and Drew Brees all increased ball velocity and arm strength upon entering the NFL. It doesn’t seem to be as permanent as people make it out to be, but isn’t the kind of thing one projects to improve a significant amount.

In terms of touch, Murray is judicious about taking pace off the ball when necessary, and like to throw bucket passes when his receivers win against man coverage. He also is smart about how the angles change at different speeds and can generally arc it when he needs to. He just has a problem of arcing it too much.

Pocket Presence: Aaron Murray has surprising inconsistency when it comes to pocket presence. Usually when players are relatively inconsistent, it can be explained by a general rule: they usually feel pressure but react too early, making some actions look preternatural and others look scared. For Murray, it’s pretty clear that he is sometimes very good at sensing edge pressure and getting away from it, and sometimes completely oblivious to it—an odd combination. Moreover, he has some games where pressure clearly gets to him and his mechanics suffer (Missouri) while he has others where constant pressure isn’t nearly as much problem mechanically (Clemson, though that was his least accurate game I’ve scouted).

Murray occasionally drifts into pressure, which eliminates space for him on his throws and exposes him to more pressure and potential sack opportunities. It hurts his mechanics, (sometimes, being rushed contributes even more), and his throws under pressure are much more inaccurate despite the fact that it looks like he’s standing tall in the pocket.

He also has a few times where he’ll overreact to pressure, lean back from it or rush his throws in response to it. Those instances are further apart than most people with pocket presence issues, but they’re there and they will be magnified in the NFL.

My bigger issue is that he manages interior pressure very poorly and has extremely inconsistent edge management (sometimes climbing the pocket, sometimes leaning away, sometimes sensing pressure, sometimes remaining oblivious). Those times he has poor pocket presence and makes mistakes are not really counterbalanced all that well by those times he has good presence, because he simply is an OK quarterback in a clean pocket.

I have minor ball security problems with him as well, sometimes in exchange and sometimes while sacked (though many of these were ruled incompletions, it speaks of a worrisome trend). It doesn’t appear every game, but it worries me a lot; much more than with anybody else I’ve reviewed. At least Manziel, who is careless about his ball carriage, still hasn’t fumbled the ball all that often. Both Manziel and Murray, however, should be careful—their low fumble stats probably won’t carry over into next year.

Field Sense: For all the clamoring about the control that Murray has in the “pro-style” offense that Mike Bobo ran at Georgia, there doesn’t seem to be as much in Murray’s control as people have been implying. That’s fine, most college quarterbacks don’t have the full arsenal of plays to call, and it’s rare that a passer has access to every play when approaching the line, like Bridgewater does.

But while Murray seems to have responsibilities for protections and presnap reads, the audibles are called from the sideline. I have seen from sources that I respect that Aaron Murray is in full control of audibles and the playbook, but watching the games for the countless times the team looks to the sideline and changes plays, or reading the comments from fans and bloggers about Murray’s frustrating lack of control at the line of scrimmage leads me to believe that he really doesn’t.

At any rate, Murray’s habit of forcing throws, combined with his long release time makes him extremely poor against zone coverage, where most of his interceptions came from this last year. He also misses defenders at times (as in, he doesn’t know where they are) or doesn’t see how they’ll react to his throw. He also likes to throw across his body, which is generally inadvisable for players that lack either arm strength or stunning accuracy, and the low velocity of those throws, along with the general inaccuracy, will create additional turnovers.

Further, one big aspect to “pro-style” work is playing under center and reading while dropping back to pass, working within a rhythm with footwork and maintaining pocket integrity. Murray took the vast majority of his snaps from under shotgun as Mike Bobo moved closer and closer to a spread-style system with four and five receivers, wider lineman splits and fewer pro-style route concepts for Murray to read through.

They’ve been doing that for far longer than people may think, and almost all passes from under center have been I-formation play-action passes, instead of non-constraint passing plays with traditional route progressions. Because of that, I think it will take longer for him to adapt to an NFL offense than people typically indicate.

That said, Aaron Murray clearly goes through progressions and is willing to scan the full field, unlike many prospects higher up than him on draft boards. He clearly looks off safeties and is willing to use his eyes to move the defense around. He’ll hold defenders in place and will anticipate receivers (though he is late on them a lot of times) getting open against those defenses.

His progressions are quick and generally correct, though he’ll move on from an open safer receiver in his progression in order to see if more aggressive option is open—and that can lead to mistakes.

Nevertheless, his ability to master some of the more subtle crafts of quarterbacking shouldn’t be ignored and it’s sometimes just pleasant watching film of him playing particular defenders like a fiddle when they aren’t doing the same to him.

Scrambling/Running: Like Derek Carr’s athleticism, extremely underrated because of his offensive system. Would be effective at running in any system that dosed in two or three quarterback runs a game and shouldn’t limit him from any particular play or scheme in the NFL. But that’s only one-off, straight-line speed.

Murray isn’t an accomplished “runner” in the sense that he has great vision, agility or patience to really run like a good runner should, but that is mostly judging against other runners at the quarterback position. He is much better than the average pocket passer as a runner and should be used in that way from time to time.

As a scrambler, he’s functionally OK but doesn’t create big gains or consistently get away from pressure to be considered a great scrambler.

Intangibles: It is once again difficult to speak to this, but I feel obligated to include this. In order to defer my made-up responsibility on this, I’ll just quote Scouts, Inc.:

Holds a career record of 35 and 17 as a starter. Respected by teammates and coaches. Adequate leadership skills. Will get vocal when he needs to. Strong work ethic and willing to put in the time. Enjoyed the party life early on but has matured as career progressed. Very good student (named to SEC Academic Honor Roll multiples semesters). Showed improved poise in big moments as a senior rallying fourth quarter comeback against LSU, Tennessee and in the Auburn Hail Mary game (loss).

Good enough.

Primary Concerns: I’m really confused as to why Murray hasn’t consistently gotten better as a passer (I don’t mean statistically) over the course of his time at Georgia. Unless his 2010 game against Auburn is a fluke, he was phenomenal (even though some of his throws have terrible footwork), even if you account for the fact that he was throwing to A.J. Green, Tavarres King, Orson Charles and Kris Durham. The ball had more zip and spiraled better, even with sidearm throws. He displayed incredible arm strength, quick and correct decisionmaking and only needed to clean up the lower half of his body on throws. He was unafraid of pressure (but a bit stupid about it sometimes) and a great scrambler. What happened? His ball placement even was better.

There’s a chance it was a fluke. His 2011 against South Carolina was abysmal (aside from, interestingly enough, an incredible scramble), but I’m still worried about why his delivery looks worse now, and why his accuracy doesn’t seem up to his redshirt freshman self. Even his other 2011 tape (say against Auburn again or Michigan State) looks good. His 2012 tape isn’t nearly as stellar (I looked at his game against Tennessee and South Carolina. I also looked at the SEC Championship game against Alabama, where Murray put the third-most efficient passing performance Alabama saw that year, despite Murray’s poor box score—it looked like a decent game from the QB at a quick glance, with a glaring error), but some of it looks like it could be an improvement over some of the 2013 stuff I saw.

So, without a great explanation—why would the 2010-2011 stuff look better than the 2012-2013 stuff?

I cannot emphasize how much his weakness against zone coverage bothers me. He will too often throw the ball close enough to a defender that they can close on the ball, and he usually doesn’t see them. Against man coverage, Murray has a decent instinct of where to throw the ball, but seemingly cannot handle those players that read his eyes, as good as he is at masking his decisions.

The fact that the ball is often slow out of his hands when playing risky against those zones exacerbates the problem. Already making ill-advised decisions, he needs more zip on the ball to follow through on them.

Aaron Murray’s ACL injury is one of the biggest concerns people have about him entering this draft, and that makes a lot of sense. After seeing what Robert Griffin III turned into after his knee injury, there’s a good reason to be wary. It’s true that Murray showed well at his Pro Day and that ACL treatment seems to have improved by leaps and bounds in recent years, but it introduces more uncertainty into his prospects, and it’s not something that can be waved away easily.

If we accept that he’s not guaranteed to return to his former self, we should at least estimate a probability. Based on what we’ve seen, something like 80% makes a lot of sense if we’re being generous. Jamaal Charles and Adrian Peterson came back, but it took a lot of time for Darrelle Revis to return to his former self and some players didn’t meet those same standards (Kyle Williams of the 49ers wasn’t great before his injury but was definitely worse after it, while Jake Ballad has done nothing).

If 80% of a backup-quality player is what you’re getting (or an 80% chance of getting the player you scouted to be a backup-quality player), it is difficult to justify a good pick.

One last note: Murray’s height and short arms have come up a few times, and while I think the arm length is relevant to the analysis of whether or not he can improve his arm strength (his earlier tape implies that he’ll be able to, so not a huge worry), his height is only relevant if his release point is too low (it’s not) and whether or not he slides to open lanes or finds other ways to account for his height. It may, in some small part, contribute to the batted passes we see, but I think the fact that he fires low in general has a greater impact.

Conclusion: Based on what I saw in 2013 on tape (before other concerns), I would give Aaron Murray a late fourth-round grade and would not except to anyone who graded him as a fifth-round prospect. I was not as careful to break down his 2010-2011 tape, but if my initial impressions match potential deeper work, Aaron Murray could be worth a low first-round pick. He still wasn’t 100% in sensing pressure and there were some ball placement concerns, but he had more accuracy and arm strength (significantly more arm strength) than the seven-game review of 2013 (and that was before the injury) and the quick look at 2012.

That’s a loose grade not subject to the rigor that I gave the 2013 tape, but worth thinking about. Because of that, I would move Murray up off of my 2013 evaluation (by a round)—something is definitely there worth investigating, even if we’re willing to say that he had more to work with when he looked better. We could just as easily say his high drop rate may be attributable to a terrible supporting cast (I don’t really think so) or that his chemistry was too far off with a rotating corps or any number of other things. Basically: if we’re downgrading him for his good supporting cast in previous years, we need to ask why we wouldn’t upgrade him for his poor cast this year.

But to finalize the circular arguments, one would need to explain the difference in statistical output in 2012-2013 if his supporting cast was the reason he looked weaker. At the end, it’s not worth the chance, especially with an injury in the books. Because of that injury, I’d bump him back down one more round to the fourth round.

To reiterate: fourth-round grade based off the tape, but he gains a round because of previous work and loses that round due to injury. I like him best as a backup in a rhythm-oriented offense, such as the Coryell offense Turner will run, but that doesn’t mean I think he has starter potential.

You must be logged in to post a comment.