Update: Teddy Bridgewater Against the Greats Rehashed

Earlier this year (December 4, before his last four games and omitting the hot streak he finished the season on) we looked at how Teddy Bridgewater compared to some of the greatest quarterbacks to play the game, as well as many former Vikings quarterbacks. Since then, Teddy had been on fire to close the season and finished the final five games with the second-highest completion rate in that time (behind Tony Romo), the seventh-highest yards per attempt, the eighth-highest passer rating and the seventh-highest adjusted yards per attempt (out of 30 quarterbacks who threw the ball at least 100 times in that span). In those five games, he ended up as Pro Football Focus’ second-highest graded quarterback, behind only Aaron Rodgers.

It’s safe to say that the statistics in the second-half of his season have buttressed those in the first half, providing Bridgewater with more statistical support in these kinds of comparisons.

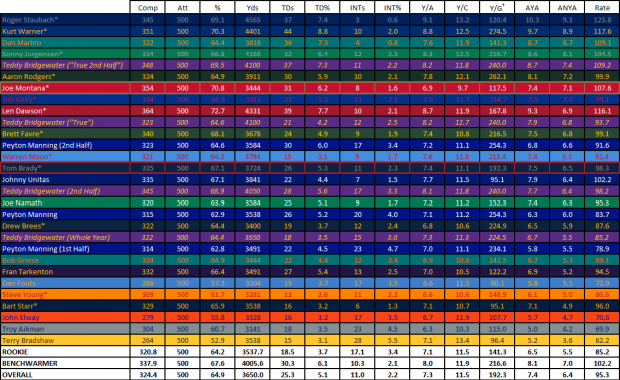

As a refresher, I’ll quote the original piece to describe the methodology, then show you the updated tables:

[H]uman performance tends to be normally distributed, and even though NFL quarterbacks are theoretically at the tail-end of the “ability to quarterback” curve, their performances in the NFL also tend to be normally distributed. That means we can simply take the distance from the mean of that year (measured not in the original unit, like yards per attempt, but in “standard deviations” so that a certain percentile of performances will always fall below a common standard—so a performance 1.0 standard deviations above the mean will have 84.1 percent of performances fall below it) and apply it to 2014, so we have a common set of units. Further, because volumetric totals will be different by year and so on, it makes sense to give everyone a number of attempts that matches 2014 so we can get a better grasp of what the old numbers would mean. I picked 500 attempts (and pro-rated Teddy to 500 attempts for the comparison).

So, after adjusting for era and attempts, we can compare Teddy Bridgewater’s rookie season to the first season of every Hall of Famer who has played in the 1960s on up. “First season” is difficult to define, of course—if someone starts one game, does it count? What about five? What if, like Don Strock in 1981, you didn’t start any games, but you threw significant passes in all of them?

Do we do it by attempts? Starts? 34 attempts can be someone’s first action in the NFL, but it’s not a meaningful representation of how good they are. Christian Ponder’s first 34 attempts in 2012 were really, really good—he averaged 8.9 yards per attempt and threw no turnovers (and in his next 34 passes, he continued not to throw picks, threw two touchdowns and had 8.5 adjusted yards per attempt).

Generally speaking, yards per attempt should stabilize around 200 attempts, so that’s what I chose.

All this means is that we can compare across eras in order to account for the fact that there were periods in NFL history it was easier to throw and other periods where it was harder to throw. Because Hall of Fame quarterbacks (and wins) tend to be the result of in-era comparisons instead of acontextual tallies, this is the best way to look at how players played for their time.

I then did a few other things, not all of which are statistically sound or perhaps fair. The first thing is a useful comparison if only because Teddy Bridgewater turned it on in a big way in the second half of the season, and that may be relevant to his progression as a passer and intuitively is closer to his “true talent” as it relates to future performance in the NFL. In the graph below, there’s a Teddy Bridgewater (Whole Year) dataset, which predictably just takes his entire year and prorates it to 500 attempts. There’s also a “2nd half” dataset that assumes Teddy performed like he did in the second half of the year for the full year, just to take a look at how it would compare (perhaps more interesting to compare to first-year quarterbacks who were not rookies, marked with an asterisk).

I’ve argued in the past that improvement in a small sample at the end of the season historically does not correlate to good performance next season; it’s much more likely that a player plays to his career averages than “carries over” momentum from the end of last season. This was relevant to Christian Ponder, who at the end of 2012 improved over the course of his final four games and put together a truly impressive performance in the Green Bay game. One can track the improvement by looking at adjusted yards per attempt, which takes into account touchdowns and interceptions. It is a different beast, however. Ponder’s performance was below league average in all but one of the games—it was more likely that his improvement was the result of regression to the mean than an epiphany, especially because he only played one good game. Ponder outperformed his Week 12 and Week 13 performance twelve times before those weeks, so it wasn’t meaningful improvement.

Teddy Bridgewater’s case is a bit different, where his 8th game had three poorer performances and four better performances prior—before he went on a five-game streak where none of his games were worse than the game against Green Bay (which by itself was not a bad performance). Further, half of the relevant data for Bridgewater (the final six games) is more meaningful than four of Ponder’s games, which at that point not only included a number of terrible games touted as good, but only comprised of 14 percent (or less, depending on whether one counts the substitute performance against Chicago) of the available data on Ponder.

That’s not a strong case that the final uptick in performance is sustainable, but I think because Ponder’s late-season “improvement” in 2012 wasn’t even improvement, the cases are not analogous. Either way, you can choose to count it or not. I previously mentioned that Peyton Manning improved massively in his final eight games, so I included Manning’s second-half-season statistics as well (adjusted for era).

With eight games under his belt, Peyton Manning’s team was 1-7 and he himself was passing at a 64.5 rating, 31st of 36 quarterbacks. His adjusted yards per passing attempt was 4.7, 30th of 36 quarterbacks and he was often referred to as a “struggling” quarterback with 11 passing touchdowns and 16 interceptions, though the praise of volumetric statistics ran rampant throughout sports media at the time (as you’d expect).

In the second half of the season, Manning’s passer rating was 78.1, 14th of 31 quarterbacks who threw at least 100 passes in the final eight games of the season. He had a 15:12 touchdown-interception ratio and ranked 21st in adjusted yards per attempt in that time.

The final thing I’ve done to Teddy Bridgewater’s data for comparison’s sake is remove some of the noise. For the entire month, I and a number of other fans have noticed that Teddy Bridgewater seems to be getting a bit of a short shrift when it comes to statistical accounting, both because he seems to lose touchdowns he’s “earned” and because receivers keep on giving him interceptions by deflecting the ball into defender’s hands. This is perhaps unfair because I didn’t do this to any other quarterback, and I don’t know if I’m an objective evaluator. I also did not remove touchdowns that he may not have deserved (if it deflected off of a defender into a receiver’s hands or should have not been called a touchdown but was incorrectly ruled one), so it may not be a “true” accounting of his performance, even though it is labeled as such. I added three touchdowns—the one Charles Johnson fumbled to Jerome Felton against Detroit, the one Greg Jennings dropped this Sunday in the end zone, and the weird ruling against Miami that denied Chase Ford the touchdown.

I added two interceptions, the one that Johnthan Banks dropped in Tampa Bay and the one Jared Allen dropped last week. I don’t recall any others. I took away four interceptions—last week when Kyle Fuller ripped the ball out of Cordarrelle Patterson’s hands, two of Matt Asiata’s deflections (against Miami and the first game against Detroit) and the Hail Mary attempt against the New York Jets. There are other ambiguities (two with Charles Johnson, one with Cordarrelle Patterson and so on), but I thought they were more on Teddy Bridgewater than the receivers and didn’t want to include marginal cases. As it is, I’m pushing it by making a judgment call on Chase Ford. The final thing I did was adjust the receiver drop rate to league average, so that the completion rate matches what would happen for a quarterback who had as many drops as the average passer but the same accuracy.

There is a whole season “true” statistic and a 2nd half “true” statistic in there for comparison’s sake. At the bottom, when I compare Teddy to former Vikings quarterbacks, you’ll see I’ve created a “true” statistic for Christian Ponder as well (he was denied three touchdowns his rookie year, but I only added one because he later got a passing touchdown on two of those drives). Without further ado, here are the comparison tables!

QBs with an asterisk played their first year as non-rookies. The only statistic not adjusted for era is yards per game. For a clearer or bigger picture, click on the image

Bridgewater’s rookie year (unmodified) beats the median Hall of Fame rookie quarterback performance in completion rate, interception rate, yards per attempt and adjusted yards per attempt. It meets the adjusted net yards per attempt metric for rookie Hall of Fame quarterbacks and just misses the touchdown rate mark. For all HOF quarterbacks in their first year, Bridgewater’s whole year statistics fall behind if only because there were some stellar performances by quarterbacks who started late, like Roger Staubach, Kurt Warner, Sonny Jurgenson and Aaron Rodgers. Still, he’s tied in yards per attempt.

Of course, when you look at the second half of his season or his “true” statistics, he meets the exceedingly high standards of the whole dataset instead of just rookies and winning in a number of categories. If you want to look at Bridgewater against just rookies, here you go:

Definitely a favorable comparison. If you want to look at markers of playing style (completion rate, yards per completion, adjusted net yards per attempt, etc.), then the closest stylistic comparison is Drew Brees, followed closely by Peyton Manning. The Drew Brees comparison rings particularly true after the fascinating parallels between the two.

The statistical comparison tool—which does not take into account important features like mobility, scrambling, time in pocket and so on—finds that Aaron Rodgers, Troy Aikman (another Norv quarterback!), Len Dawson, Dan Marino, Sonny Jurgenson and Roger Staubach are the furthest from him, less because of style and more because of talent. Aikman didn’t flash very much of it his rookie year, and the others outperformed Teddy in their first years by some margin (with only Dan Marino doing so as a rookie).

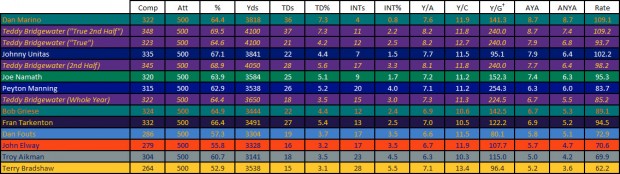

We can also look at Vikings quarterbacks of yore:

Reminder: all colors are from the team they originally played on, and those teams’ colors at that time.

Certainly nothing definitive, but definitely encouraging.

You must be logged in to post a comment.